‘The “chaudières” of Nonceveux, near Remouchamps. The first “chaudière” at the confluence of the Ninglinspo with the stream of the Grandes-Fanges, near Nonceveux, in abundant water regime.’

Document, Unknown Author in Les cavernes et rivières souterraines de la Belgique étudiées spécialement dans leurs rapports avec l'hydrologie des calcaires et l'hygiène publique : La Grotte de Remouchamps et le Vallon des Chantoirs. Extrait (Chapitre X), Ernest Van den Broeck, Édouard-Alfred Martel, Edmond Rahir (1907), edited by the authors.

Bibliothèque Ulysse Capitaine, Town of Liege.

Document, Unknown Author in Les cavernes et rivières souterraines de la Belgique étudiées spécialement dans leurs rapports avec l'hydrologie des calcaires et l'hygiène publique : La Grotte de Remouchamps et le Vallon des Chantoirs. Extrait (Chapitre X), Ernest Van den Broeck, Édouard-Alfred Martel, Edmond Rahir (1907), edited by the authors.

Bibliothèque Ulysse Capitaine, Town of Liege.

In the province of Liege (Belgium), Lignes de flottaison [Waterlines] explores our relationship to water, in particular to the Meuse river and its tributaries. The corpus, developed from documents collected (from various archive locations) and photographs taken, composes an eclectic iconographic nebula which outlines in snatches a historical, topographical and poetic drift. The work questions the effects of time on places, images, and our imaginations.

Read the text of Sophie Soukias at the bottom of the page.

Read the text of Sophie Soukias at the bottom of the page.

Meuse, 1930 Toxic fog, site of the Société Métallurgique de Prayon,

Engis.

Document, Unknown Author, Photographic Print.

Albert Humblet Collection.

‘Pumping Station, Jemeppe-sur-Meuse, Liege.’

Document, Unknown Author, Photographic Print.

Archives of AIDE, Association Intercommunale pour le Démergement et l'Epuration des communes de la province de Liège.

Gueule, Plombières.

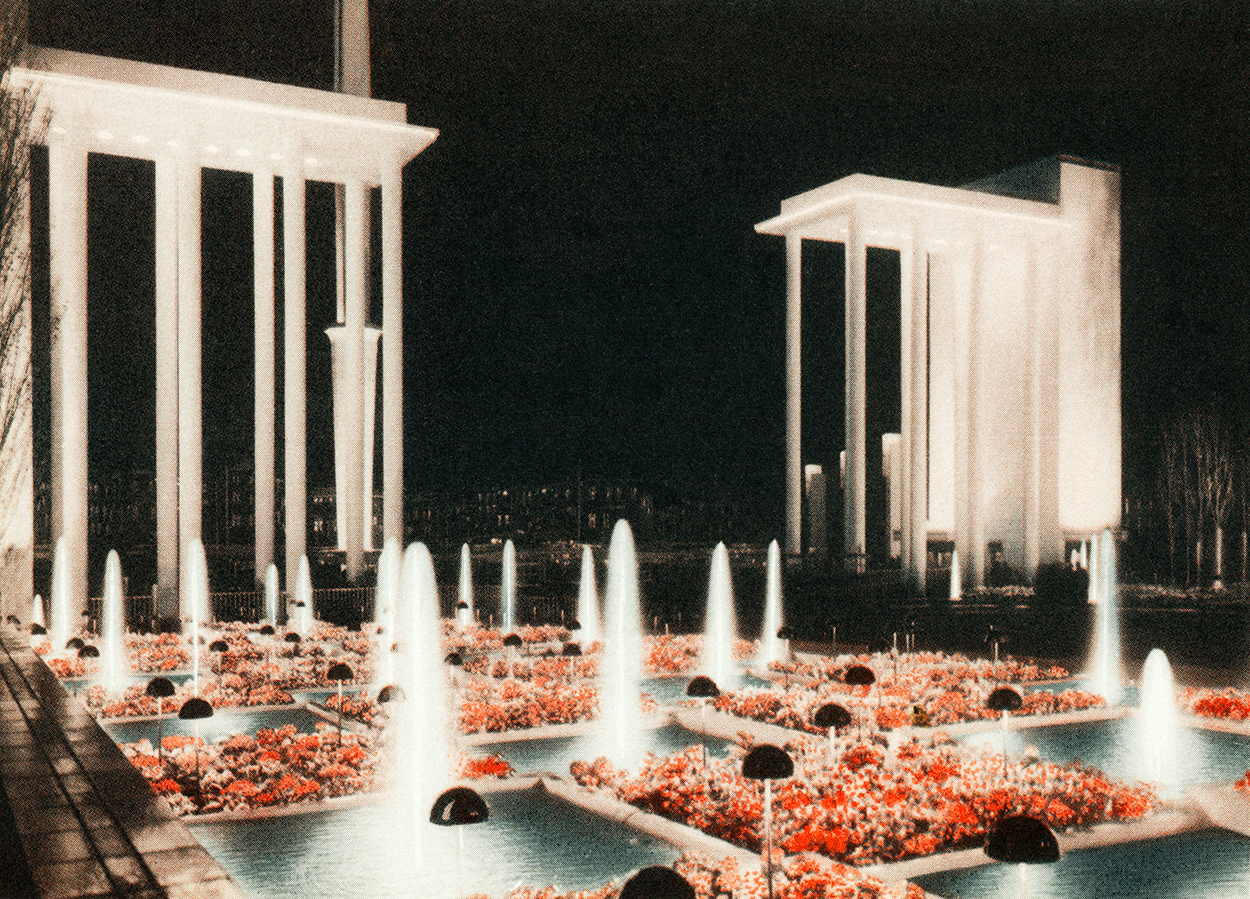

‘Official Postcard of the Liege International Exhibition of [Water Techniques] 1939. Lighting of the floral bed displays.’

Document, Unknown Author, Postcard edited by G. Sentroul.

Meuse, Liege.

Document, Unknown Author, Postcard, Unknown Editor.

‘Xhavée Water Outfall, Wandre, Liege.’

Document, Unknown Author, Photographic Print.

Archives of AIDE, Association Intercommunale pour le Démergement et l'Epuration des communes de la province de Liège.

‘American Bombing on May 25, 1944 [on Ougrée, Seraing].’

Document, Unknown Author, Photographic Print.

Archives of AIDE, Association Intercommunale pour le Démergement et l'Epuration des communes de la province de Liège.

Meuse, Liege.

Meuse, Île de Franche-Garenne, Hermalle-sous-Argenteau, Oupeye.

Tilff, Esneux.

Meuse, Grand Palais, Coronmeuse, Liege.

‘The rocks of ‘The End of the world’ in Colonster seen from the Castle.’

Document, Unknown author in Les guides scientifiques du Sart Tilman, 1. Géologie, Collective (1974), edited by the University of Liege.

Bibliothèque du patrimoine souterrain, Maison de la spéléologie, Namur. Photocopied copy.

Meuse, Coronmeuse, Liege.

Hautes Fagnes – Eifel Natural Park.

Gileppe Dam, Hautes Fagnes – Eifel Natural Park, Jalhay, Baelen.

Ourthe, Angleur, Liege.

‘Model of the Port of Liege exhibited at the Palais des congrès of Liege (1958).’

Document, Unknown Author, Photographic Print, Ministry of Public Work and Reconstruction [Belgium].

Archives of the Port of Liege.

Storm water reservoir, Ans.

Document, Photo Robyns Reportage Photographique, Photographic Print.

Archives of AIDE, Association Intercommunale pour le Démergement et l'Epuration des communes de la province de Liège.

‘Boat crossing.’

Document, A. Goeydan in Cordées de la nuit. La spéléologie en Belgique, Jean-Pierre Van den Abeele (1954), edited by Arts et Voyages, Lucien de Meyer (Brussels).

Bibliothèque du patrimoine souterrain, Maison de la spéléologie, Namur.

‘Liege. – The Ruins of the Maghin Bridge.’ [1940].

Document, Unknown Author, Postcard edited by Légia, Liege.

Meuse, Bridge of Arches, Liege.

‘Incised inscriptions of the floods levels in 1571, 1643, 1740, 1850 and 1926 on a pillar of the Saint Paul’s Cathedral of Liege.’

Document, Unknown Author, Photographic Print.

Archives of AIDE, Association Intercommunale pour le Démergement et l'Epuration des communes de la province de Liège.

‘Gileppe Dam. The lake in times of drought.’ [1921].

Document, Unknown Author, Postcard edited by J. B. Dejardin-Cuisset, Bethane.

I.

Most of the people of the cave still called the event an “atmospheric accident.” Nothing proved, however, that the disaster had been triggered by a meteorological phenomenon. Rather, the scientists (there were three of them) agreed that the deadly weather was the symptom of a catastrophe of a far more ominous scale but about which they knew little if anything.

The founding myth of the cave had it that the survivors of the atmospheric accident (five women, four men, and a three-month-old baby) were carried to the cave by an overflowing river into which they had been flung by lightning. From this episode, they remembered nothing. The shock of static electricity had burnt up all their memories. The tingling in their limbs, the eye lesions they each suffered without exception, and their soaked and ragged clothes had fuelled the “atmospheric accident” hypothesis. This accident would obsess future generations cut off from the history of their ancestors.

II.

Only about twenty period photographs, recovered from the handbag of one of the survivors, formed the traces of the world before the accident. How they had stayed intact, no one could explain. The woman in question, a delirious old lady, was to take the secret of these images with her just days after being stranded in the cave.

III.

These images, the boy knew them by heart. They formed the depressing mythology of his young civilisation, unable to live in the present until it could elucidate its past. He had seen over and over these images in black and white (for a long time, he had believed his ancestors incapable of seeing in colour) of lifeless water temples, flooded houses, and the bombarded river, to the point of being sickened by them.

Only one image was still able to move him: that of a waterfall whose cascades crashed into a sea of white clouds. The boy had often wondered if it wasn’t the absence of human technology that made this image possible to look at. Perhaps he liked it too because it was composed of the same materials as the cave: rocks and water.

IV.

Haunted by the fear of a new “atmospheric accident,” nobody had dared venture outside of the cave. Nobody with the exception of one man: “The Gerlache.” On a makeshift boat, he had sailed upstream to the source of light that lit the long corridor of the cave. He had never returned.

Exiting the cave was child’s play. It was fear of the world outside that paralysed even the most reckless. The scientists had wound up resorting to a system for capturing sound pinned to the walls of the grotto: the signal from outside received by the microphones allowed for the reconstruction of the shapes and colours of the depopulated life around the cave.

V.

The weakest personalities, the most sensitive spirits, couldn’t manage to content themselves with these images of desolate landscapes without any human souls, and found themselves at the mercy of every charlatan claiming to be bringing back lively stories from the external world (present, past, and future) with which supposedly they had had telepathic contact.

VI.

The boy had been warned many a time not to pay attention to these dream sellers. He couldn’t prevent himself from becoming caught up in the flow of their magical words. To the point that he regretted his lack of attention and his inability to record all the details that made those stories so real and so deliciously believable.

His favourite story was, unsurprisingly, that of the “atmospheric accident,” renamed by its author: “Waterlines.” Always the same, it started like this: During the day of April 24, the particularly stifling atmosphere (and yet the thermometer only indicated 22 degrees) foreshadowed a storm. When this burst upon the region, all creatures, animals and humans alike, had been bathed for the previous fifteen minutes in a pitch-blackness now and again crossed by blinding flashes that strobed throughout the entire cap of the sky. Around 9:15 PM, accompanied by increasingly heart-shattering cracks, successive rain showers sluiced down upon the city and the region veritable bundles of water and hailstones. The whole police force and all the firefighters were already in a state of alert…

VII.

Every night, before falling asleep, the boy would stare for a long time at the mesmerising light that twinkled at the end of the cave tunnel. In the moment of closing his eyes, he would promise himself not to look at it ever again. The next day, he would have forgotten his promise.

Text by Sophie Soukias, 2021

Translation by Ârash Aminian Tabrizi

en Piste ! Exhibition at La Boverie, Liège, Belgium, 2022

Exhibition during the Xth Biennial of Photography in Condroz in Régissa, Marchin, Belgium, 2021

No part of this website may be used, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior written permission. Maxime Brygo, 2007-2025